Despite the simplicity of the name, the warm up phase of a class is more valuable than you may think.

Aside from doing the obvious (warming you up) the warm-up is a period where you can focus on things like positional efficiency (eg. correct set up and finish positions), correct movement patterns (eg. fixing early arm pull, core to extremity) and mobility/flexibility, without the distraction of fatigue or competition. It is also a chance for us to provide you with more technical and detailed coaching in a setting where you are able to take in the information and process it – because lets face it, when the clock gets going there are few people that have enough head space available to receive technical coaching while trying to get the job done.

Here are some tips that might help you get more out of your warm-up (and therefor more out of your workouts):

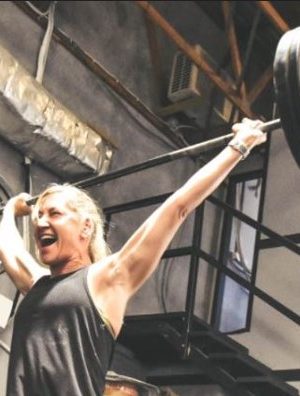

– Break complicated movements up into segments. We do this frequently with Olympic lifting but it can be done with almost any exercise. Think shrug, high pull, muscle snatch, overhead squat, drop snatch etc. It makes sense that if you can get good at the individual segments of a movement, then you have a much greater chance of improving the full movement when you put the segments back together.

– Hold positions. Very few people can claim to be able to hold the correct start and finish positions for a movement yet they wonder why they can’t move correctly between the two. If you can’t hold the start or finish position of a movement with an empty barbell without discomfort then you are in for a rough ride when you add weight to that bar.

For example, if you are doing thrusters, rather than just get a bar and do lots of thrusters; sit in the bottom of the front squat and focus on an upright torso with active hips and only when you achieved the best position possible, should you drive the bar up overhead and focus on achieving lock out with a neutral spine and engaged glutes and lats. Once you feel that you’ve achieved good positions, then add repetition to the equation.

– Don’t go up in weight too quickly. Here is a classic example: 15 minutes to work up to a heavy clean and jerk. Athlete X has a 1RM of 100kg. They grab a bar, put some 20’s on and rip a couple of reps of the ground ignoring any faults because they KNOW if 60kg feels bad, then 80kg will feel better. After a few crappy reps at 80kg, they bump it up to 90kg and with 11 minutes to go, we’re right where we want to be – at 90% of 1RM with terrible form and an almost inevitable disappointment coming their way. After spending another 7 or 8 minutes trying to match their previous 1RM without success, they decide that maybe today should just be a technique day and strip it back to 80kg where they might get one or two good reps in before time runs out.

A better scenario would be to set yourself a few personal goals to achieve in the session and let increases in weight be the reward for achieving those goals. For example, you might be working on the landing position of the split jerk and you can only go up in weight when you have achieved your movement goal. Good rep = go up in weight. Bad rep = stay there until you get it right.

– Work mobility. For a generally mobile person, the movements may suffice in getting your body ready to hit the positions of the workout but if you have specific deficiencies in your flexibility then getting out a resistance band, or a lacrosse ball, or roller is often far more effective at targeting these areas.